- Name:

- Koharu Tatekawa

- Profession:

- rakugoka (Japanese traditional storytelling/comedy performer)

- Current Residence:

- Koenji, Suginami, Tokyo

INTERVIEW WITH KOHARU (RAKUGO PERFORMER)

Rakugo is type of traditional Japanese comedy, based on storytelling with little to no props aside from simple folding fan. Most performers rely completely on their storytelling abilities, and often show an exchange in dialogue between characters simply by turning their head to a different angle. A Japanese performance art with a long history, very few women have entered into this profession. Koharu Tatekawa is a woman from Koenji who broke into this traditional performance art, and has even been performing abroad. We spoke to Koharu about these experiences and present our translated interview here.

[published February 2020]

Experience Suginami Tokyo: Koharu-san, thank you so much for having an interview with us. How long have you been a rakugo performer?

Koharu Tatekawa: It was in March 2006 I started my apprenticeship to become a full-fledged rakugo performer. I spent my first seven years as zenza, a disciple working in daily direct contact under his or her master. Seven years ago, I was promoted to futatsume, which meant that I could from then on perform independently from my master.

EST: What was your original inspiration for becoming a rakugoka?

KT: Until I started training as rakugoka, I was studying cell culture at the graduate school of Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology. During my time there, I joined the university’s ochiken, the “Rakugo Club”. That was when I took an enthusiastic interest in rakugo. I also learned how fun it is to perform rakugo, and eventually decided to become a rakugoka myself.

EST: I heard that female rakugo performers are very rare. Was it difficult to enter in this profession? What were some difficulties or hardships you experienced as a female entering rakugo?

KT: In 2006 when I decided to start training under Danshun Tatekawa, there were only about a dozen woman rakugo performers, so they were indeed quite rare. At the time, there was not a single woman performer in the Tatekawa School led by Master Danshi Tatekawa. Although Master Danshi never allowed women to train directly under him, he was unaware of the fact that I am a woman when I started my training, greeting his disciples, i.e. all disciples who trained under Danshi along with my own master Danshun. One year had passed without the issue being brought up, and once he became aware that I am a woman, he had to allow me to train in the Tatekawa School. That’s how I have been able to be part of the rakugo community.

EST: You live in Suginami and often perform in Koenji. Do you feel that area is good for you since it is an artistic area also known for the Engei Matsuri rakugo festival?

KT: I have lived in Suginami for one and a half years, and the owners of shops in Koenji have always been very kind to me since when I was assisting rakugo performances in my first years of training as zenza. In Koenji there have been a lot of shops that have been holding rakugo events for a long time, and Koenji Engei Matsuri (Festival) is the outcome of those events. I am always grateful to Koenji because of those restaurants and bars, the shopping streets, and the audience are always enthusiastic and generous in supporting artists of all kinds.

EST: You have had experience performing in front of foreigners thanks to Rakugo Without Borders. Without the supertitles, those who cannot understand Japanese perhaps would be completely lost watching your performance. How do you feel about the opportunity to present rakugo to foreign audiences?

KT: Classical rakugo mainly deals with the daily lives of the common people during the Edo and Meiji Periods of Japan, and also includes lots of Japanese puns or gags. So, I suppose if you are not proficient in Japanese language, and partially also history, to a very high level, you may not be able to enjoy rakugo that much. I initially thought that audiences abroad who didn’t know the stories or could not naturally follow the dialogue would only be reading the supertitles above my head all the time, but to my surprise European audiences reacted to my expressions and gestures so well that the performance itself felt very natural, just like any performance in Japan, really. It is because of the excellent translations which make these performances possible – thanks to Rakugo without Borders that both performers and audience can connect with each other.

EST: You have had two tours abroad. Where did you go and how was your experience?

KT: My first time performing abroad was with my Master Ichinosuke Shunpūtei. We went to Belgium, Poland and Finland. Last year I did shows in Germany and Poland. During both trips we performed rakugo in Japanese with supertitles in the respective local languages showing on the screen above us. Next to our performances, we had opportunities to do sightseeing, try different kinds of food and experience the differences in languages. We were able to learn the diversity of culture, nationalities and history, since European countries actually have land borders – Japan only has maritime borders. I found it a very interesting experience. Thanks to my experiences in Europe, I now communicate more directly when talking to non-Japanese. I also realized that a nuance of rakugo in Japanese language is that it tends to make audiences laugh more by insinuation.

EST: How did the foreign audiences abroad react to your performance? With the help of the supertitles, could they laugh at the same points that Japanese laugh at?

KT: Before performing in Europe, I was wondering if foreign audiences would be able to understand rakugo, but they laughed a lot and enjoyed my performances. In many cases I had an even greater response from them than Japanese audiences. This was also because of the excellent supertitles. Although the audience were reading the supertitles, at the same time they were observing our expressions and gestures. It was clear they enjoyed our performances. Japanese puns seemed to have been a bit difficult, but they did respond to the range of emotions, for example dialogues between couples or the relationship between a father and his son. They also understood the situations that were intended to be funny, like when a person made a stupid mistake and felt embarrassed. I felt that local audiences showed the same response as Japanese audiences. In Wroclaw, Poland, there is a large number of rakugo fans now. The timing they laughed and manner in which they laughed were practically the same as in Japan.

EST: Of course Japan is the home of rakugo, though it may not be very popular among young generations. What are your hopes, goals, or plans for promoting rakugo in Japan? How about for rakugo abroad?

KT: For a long time, Japanese thought of rakugo as something that elderly people enjoy, but in recent years it has become more popular among young people. There are young people outside Japan who like anime or kimono, and I hope they can enjoy rakugo as well. I believe that the rise of social media can promote rakugo both within and outside Japan. To contribute to this, I myself as a performer must put more effort into honing my craft.

EST: We wish you all the best of luck continuing your journey in rakugo. Is there anything else you'd like to say to our readers?

KT: At present, there is not only a growing number of young performers – there are also many popular masters – there are many opportunities to experience both classical rakugo repertoire set in Edo or Meiji as well as modern rakugo set in contemporary Japan. There are more and more female rakugo performers who are all very different. There are hundreds of rakugo performers in Tokyo and I am sure there’s one to match your taste. It may take some time – if you cannot connect with rakugo watching it the first time, please don’t give up just then. Watch a number of performers, notice their difference in performance – I am sure everybody will eventually find their favorite performer.

Koharu-san

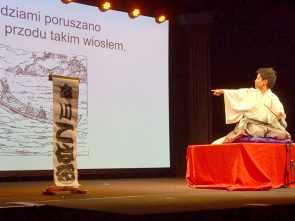

Koharu performing on stage in Europe

Koharu performing the story “Toku the Boatsman” in Poland with Polish surtitles provided by Rakugo Without Borders

Rakugo performers do not move from their small pedestal during the performance and must express everything in a small space, without any props or costumes

Rakugo performers use their sensu (fan) to aid gestures. It can symbolize anything from chopsticks to an oar, as seen here